The prospect of getting into Linux may seem daunting at first. Especially for someone who has spent the bulk of their life using the ever so user-friendly Windows operating system. Yet, once you’ve opened yourself up to the world of Linux, it will be ready to welcome you with a host of free open-source software that you can use on any personal computer. The question you’ve got to ask yourself is “Why should I get into Linux?” If you already use a certain operating system like Windows or Mac, is there really a point? Think of it as gaining a new skill set. Learning about Linux adds another arrow to your computer knowledge quiver. Soaking up more knowledge on a subject is never really a bad thing. There’s also the unmitigated fact that Linux is more secure than most other operating systems. Not to mention that there is still a demand for UNIX/Linux users in the workforce.

A Beginner’s Introduction to Linux

There are hundreds of active Linux distributions, and dozens of different desktop environments available to run them on. Things in Linux work differently than the likes of Windows and Mac, including everything from software installation to hardware drivers. Understanding every little tidbit about Linux prior to jumping into using it is not necessary, but it wouldn’t be a beginner’s guide without touching on a few key things that may help you in the long run. The first of those being “What is a kernel?”

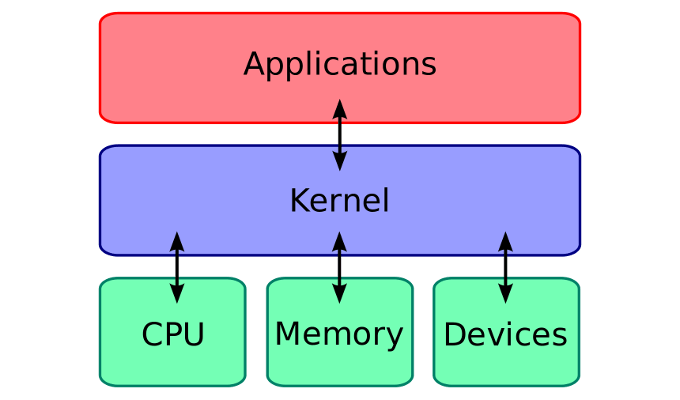

Linux Kernel

All operating systems have a kernel. The kernel of an operating system is an essential core component that provides basic services for everything within the operating system. With Linux, the kernel is a monolithic, UNIX-like system which just so happens to be the largest open source project in the world. Put simply, a kernel is the beating heart of the entire operating system.

Don’t Ditch Your Current OS

You don’t have to get rid of Windows or MacOS in order to run Linux on your machine. Some Linux distributions will allow you to install via USB drive or on a dual-boot system providing you plenty of flexibility in its use. This means that both Linux and your day-to-day operating system can co-exist side by side on the same machine.

Open Source

In the case of Linux, open-source essentially means a free alternative to the operating systems such as Windows and MacOS. It also means that users are free to alter and re-distribute the operating system as their own distribution. Linux will allow you to avoid most of the usual distractions, weaknesses, and vulnerabilities that both aforementioned operating systems tend to face almost daily.

Linux Shell

The shell is basically a user interface for Linux. You input commands into the shell and then it executes those commands, communicating with the Linux operating system. The Linux shell can use a host of varying command languages, the most well-known being BASH or Bourne Again SHell. Each language will generally have its own syntax so, as a beginner, it would be best to choose one and stick with it. It would also be beneficial to you to avoid using a GUI (graphical user interface) and opt to instead utilize the command line. This will get you more familiar with the inner workings of Linux and provide additional skills that could help you further down the line.

Choosing a Distribution

Selecting the distribution that fits your needs and criteria is the first step on your journey into the world of Linux. Unlike with Windows and MacOS, there are quite literally thousands of different distributions from which to choose. A linux distribution will take the Linux kernel and combine it with other software in order to create a complete, functioning operating system. The software added can vary greatly – web browsers, desktop environments, GNU core utilities, and much more. The more popular choices are covered in-depth on DistroWatch, which is a great place to discover the right distribution for the job. For someone with a Windows background, Ubuntu would be a fine place to start. Ubuntu strives to eliminate many of Linux’s rougher edges. However, today many Linux users have begun to prefer Linux Mint, which ships with either the Cinnamon or MATE desktops – which are both a bit more traditional than Ubuntu’s Unity desktop. Regardless, you don’t have to choose the single best version when starting out. Just stick to one of the more popular choices and you should be good to go. Each distribution will have its own website so you can head over to one of them in order to download the ISO disc image you’ll need to get started.

Burning The ISO Image

Burning the image doesn’t take much know-how and really only requires a decision be made on either DVD or USB. We recommend you take the USB option as most laptops and desktops nowadays have done away with DVD drives. A USB 3.0 drive is also more versatile, convenient, and provides a faster boot time than the likes of a DVD drive. In order to burn an image to USB, you’ll need a specialized program to make it work. Rufus, UNetbootin, or Universal USB Installer are those most recommended from the Linux distribution community. If you’ve chosen Fedora as your first distribution, the Fedora Media Writer is by far the easiest way to go.

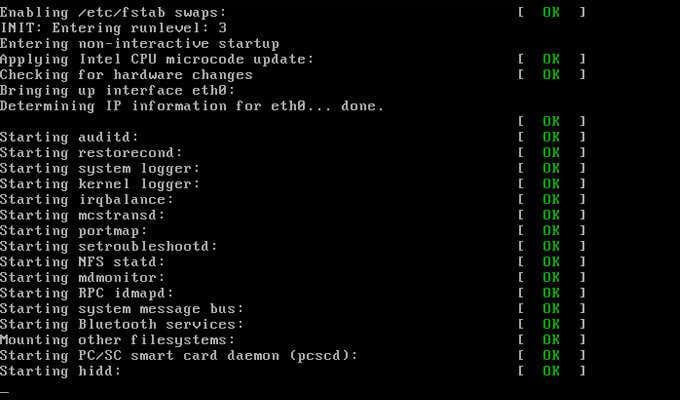

Booting Up Linux

Now that you’ve got the image, it’s time to boot it up. Plug your USB (or insert the DVD) with the distribution that you chose into your computer, and restart it. It should boot up directly, but if it doesn’t, you may need to change your BIOS or UEFI firmware boot order. Most computers are running UEFI nowadays but you’ll want to check, just in case. You can usually enter your desktop’s BIOS or UEFI by hitting either the Del or F12 key prior to Windows booting up. It’s also possible that you may need to disable Secure Boot in order to boot Linux on a Windows 10 computer. Normally, the more popular distributions don’t have an issue but if you have chosen one of the more obscure versions, it may have to be done prior to booting. Chances are good that you won’t even need to install Linux onto your computer. Instead, most distributions allow for a “live” environment meaning you can run Linux entirely from your image boot device. This is great for beginners as you’ll get to play around with the user interface and desktop to get a feel for what Linux offers. Once you’ve had your fill for the day and wish to leave the live Linux environment, you can simply reboot your computer and remove the imaged device.

Reasons To Install Linux

The primary reasons to install Linux is that running it “live” means that anything you configure in the settings, have installed additionally, and files you have created will not be maintained. Any time you remove the imaged boot device from your computer, all of that is erased. Installing Linux is simply more convenient. Play around with other distributions in the meantime until you find the one that best suits you, and install it. You can choose to remove your current operating system and replace it with Linux or you can create a more flexible choice and go with a dual-boot configuration. The installer can be found within the “live” environment.

The Linux Desktop

The majority of Linux distributions ship with the Firefox web browser already included. The other installed applications will likely vary depending on the distribution but adding additional applications is only a few clicks away. You can expect your desktop environment to have all of the standard bells and whistles: an application menu, some sort of taskbar or dock, and a system tray. Don’t be scared to click around and mess with a few things. If you’re not overly thrilled with what the desktop has to offer, almost all major distributions allow you the option of installing the desktop of your choice once you’ve installed Linux. Some distributions are optimized for a particular desktop, but changing it to fit your needs is essential to the Linux experience. You can even have multiple desktops to choose from as long as you have the disk space necessary. If you ever need help with configurations, the major distribution sites will have plenty of documentation that can easily get you on the right path. There are simply too many variations to list them here.

Installing Additional Software

You can install additional software onto your chosen Linux distribution without the need to install Linux. The major thing to worry about is that software installation on Linux works very differently from software installation on Windows. There’s no need to pull up a web browser and go on a hunt for a specific download. Instead, you’ll need to locate the software installer on your Linux system in order to make additions. For instance, if you’ve chosen Ubuntu or Fedora, you’ll be able to install the software using GNOME’s software store application. It’s literally been named Software so it shouldn’t be difficult to find. A software manager provides software repositories specifically designed to work with your chosen Linux distribution. This software will have been tested and provided to you by the Linux distribution. Think of it like an app store that is full of free, open-source software from which to choose. Just know that when you think of Google Play and Apple’s App Store, Linux was doing it first. If you can’t find the application you want in the software manager, you may have to go outside of the Linux distribution package, and get the app directly from the official site.

Driver Installation

Most of the hardware drivers required will be built in on Linux. The only closed-source drivers that come to mind you may wish to acquire are those to optimize graphical performance (AMD, Nvidia) and Wi-Fi drivers. These aren’t a necessity and everything included in Linux should be sufficient. Some distributions like Ubuntu and Linux Mint will use their hardware driver tools to recommend drivers if necessary. Then there are other distributions which will not help you install close-source drivers at all. Should you need specialized drivers, seek the help of your distribution’s documentation. Regardless, Linux should feel rather close to a Windows experience, especially if you’ve chosen one with a GUI like Cinnamon or GNOME. You should be able to find all of the more popular programs on Linux you would otherwise use on Windows.